Another political scientist, Krešimir Petković, concludes: “On the other hand, with regard to the crackdown on the far right and the parallel army it had established, several failed assassination attempts on the president of the Croatian Party of Rights (HSP), Dobroslav Paraga, are worth highlighting, as well as successful liquidations of leaders of the radical right: the founder of the Croatian Defense Forces (HOS), Ante Paradžik, was killed at the entrance to the capital (21st September 1991), and near Mostar, on the territory of a neighboring state, Blaž Kraljević, the ‘commander of HOS in Herzegovina’, was killed (9th August 1992).” Petković also bases his claims on reporting by Nacional and Wikipedia, as well as on interpretations of these events offered by a number of Tuđman’s political opponents and personal enemies. He particularly emphasized the fact that Tuđman pardoned the police officers convicted for Paradžik’s killing. Had Petković read the cited article by Tomislav Jonjić, he would have known the background of the “several failed assassination attempts” on Paraga; and had he based his work on some other newspapers or other online portals, he might have arrived at substantially different, yet equally erroneous, conclusions. By referring to newspaper articles and accusations selected according to other criteria, he could, for example, also have concluded that “Paradžik’s killing involved his former party colleague and fellow combatant Ante Đapić,” as claimed in a criminal complaint submitted to the State Attorney’s Office by the leadership of the Autochthonous Croatian Party of Rights [A-HSP]—a claim that Đapić dismissed as nonsense.

A fragment of my own somewhat older study Država i zločin: politika i nasilje u Hrvatskoj 1990-2012. [State and Crime: Politics and Violence in Croatia 1990–2012] (Petković, 2013) has found its way into one of the controversies in which the 1990s, within subsequent combative politics of history, are once again being reinterpreted. This gives me an opportunity to appear as a polemicist rather than a problématisateur—thus, as an interested party who, as far as possible, seeks to defend what he once thought and wrote.[1] Namely, in the article “The Political and Security Circumstances of the Death of Ante Paradžik,” published in the Journal of Contemporary History, Ivica Lučić, a historian and wartime member of the intelligence community, explicitly included me—incidentally, as a political scientist—among those who offer “superficial and tendentious interpretations” of Ante Paradžik’s death. Lučić, namely, interprets that death, similarly to the celebratory case of Žućo, the Hunter’s Dog, in Ćopić’s Hedgehog’s Home, as a “demise” [pogibija] (Lučić, 2016).

Lučić’s article on Paradžik’s death is thorough and meticulous. A great deal of work went into it. It is historiographically valuable—at least for those who know how to read it. With truly unusual energy—whose basic purpose is to show that the killing of a politician from the same area as the author himself (both are from Ljubuški), who found himself on the opposite side of an internal national political conflict, was at once politically logical and entirely accidental—Lučić collected archival sources on the killing of Ante Paradžik, pointed to the wartime psychosis of the early 1990s, to inflammatory tabloids, police unprofessionalism, the need to investigate various cases of death and violence separately rather than casually fitting them into political narratives, as well as to other methodological problems associated with researching the 1990s, a decade of collective conflicts, full of distortions and political myths whose caricatured media logic we unfortunately still live with today, in the discursive repetition of a tragedy that, fortunately, for now remains only a farce.

On the one hand, reading Lučić’s article reminded me of the political-media mélange I had to confront as a researcher, and of the untidiness of my own study, which often draws factual material from the same or similar sources and analyses discourse. Indeed, however difficult—and sometimes almost impossible—it may be in studies of broader scope, one ought to invest research time and energy into every controversial fragment of the 1990s. Ideally speaking, no single episode should be deprived of “thorough research and insight into the original documentation” (Lučić, 2016: 384) if one is to write a responsible and serious political history. In this, Lučić is right, regardless of the fact that historiographical and political-science studies are not the same.[2]

On the other hand, it seemed to me that precisely in the case of the killing of Ante Paradžik I had written nothing incorrect. Lučić’s strongly politically colored critique struck me as biased and misguided, and toward my study—which he incidentally treats in the quotation highlighted at the outset (Lučić, 2016: 382)—as unjust and poorly argued. Nonetheless, it remains worthy of response, if only because of the indicated qualities of the article and the deeper problems it raises, beyond polemical passions or, more finely put, the culture of public debate. Lučić’s critique begins with two formalistic remarks that do not speak to “what is” but to “where” something is recorded. In that genre, he offers an attack on a solid investigative article written for Nacional by Orhidea Gaura (2010) and on my analytical use of Wikipedia’s discourse on Blaž Kraljević,[3] whose factual substrate in the case of yet another HOS “death in action” is not in dispute.[4] This is followed by a non-specific ad hominem (I allegedly rely, according to Lučić, on a handful of “Tuđman’s political opponents and personal enemies,” but he does not specify which ones, nor what they say) and a call to read a text from the rich genre of Party of Rights schismatic literature—an appeal doubly misplaced: despite Paraga’s political histrionics, which can certainly be debated, as well as the (non)sense of his politics, claims about assassination attempts can be questioned but are by no means unfounded, especially in the context of the killings of Paradžik and Kraljević; moreover, the source that I should, according to Lučić’s benevolently patronizing tone, have read appeared in the same year as my book, possibly after it.[5]

All in all, over the past decades Lučić—who is more media-popular than his own brother—has offered a superficial and by no means subtle treatment of a fragment of a larger study.[6] It seems that the pen of one of those institute historians whose archival diligence fails to compensate for theoretical illiteracy has in this case allied itself with palpable political passion, forcing a peculiar interpretation at odds with the fact of a killing. In contrast to detailed yet selective documentation of events, Lučić succeeds in concluding his construction with a caricatured, unspecific reference to an “independent collective body” that conducted the procedure of pardoning Paradžik’s killers (Lučić, 2016: 382). Leaving aside the clichéd interpretative acrobatics at the end of the text, devoted to the “remnants of communist structures and their ideological followers” (Lučić, 2016: 383),[7]when the article descends from politicized archivistics into an unspecific political reckoning and an inability to reflect on the fact that sources generated within the state apparatus and judicial procedures are part of the story of the case rather than the whole story, the already suggested central problem of the article becomes clearly visible.

Lučić has harnessed his research energy to a contradictory interpretation that simultaneously wishes HOS to be extremist, irresponsible, and dangerous—politically harmful to state-building efforts—emphasizing Paradžik’s pro-Ustaša rhetoric (a problem “from the right” for established sovereign power, within theoretical frameworks combining Foucault and Schmitt, about which Lučić evidently knows nothing and therefore leaves them aside),[8] and that one of the leading figures of that same HOS was shot dead with Kalashnikov bullets in a car after being amicably waved through the first checkpoint on the road from Križevci to Zagreb,[9] allegedly, according to Lučić, as a mere consequence of general wartime psychosis. The tragicomic conclusion begins with the sentence: “The death of Ante Paradžik at a police checkpoint in Sesvete on 21st September 1991 was the result of a series of unfortunate circumstances” (Lučić, 2016: 384), and ends with this one: “A victim of the overall state of society and the state was also Ante Paradžik, who ‘found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time’” (ibid., 385). I was not there, nor, as far as I know, was Lučić—but it seems to me unlikely. It appears that in the 1990s many people managed, by political key, to find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time.

If we step outside the confines of the article itself, symptomatic of ideological bias is Lučić’s inconsistency in applying state formalistic criteria in establishing truth.[10] When it comes to the death of Franjo Tuđman’s father Stjepan and his stepmother Olga, Lučić, speaking in another episode of the documentary series The President, does not accept the official version given by the “investigative authorities” (“murder and suicide by firearm” due to “nervous breakdown”), but instead claims: “with very brief procedures, possibly involving some checks if they were carried out at all or deemed necessary … swift trials or killings were conducted, or killings followed by trials…”.[11] How does Lučić know that OZNA killed Tuđman’s father on the basis of a “list of enemies” he has not seen, while Paradžik—riddled with bullets at an official checkpoint after having passed through one earlier—is killed by a combination of “unfortunate circumstances”? If he seeks the answer in the character of the regime, this opens the question of how to characterize the regime of the 1990s in Croatia;[12] yet even beyond that, not even the famed advanced liberal democracies in their peacetime can unconditionally rely on a judiciary that infallibly distributes truth and justice. Political killings committed at the end of the Second World War and thereafter, and the scale of repression through and beyond the criminal justice system, are hardly comparable in scale and intensity to the moment of violent political action by sovereign power in the 1990s: someone—unlike me—may argue that their political essence is not the same,[13] but what matters here is the difference in criteria for assessing truth.

In other words, let us assume that Lučić, naively speaking, knows neither—the full circumstances of the deaths of Stjepan Tuđman Sr. and Ante Paradžik—but we can see that the methodological criteria he chooses as a foothold of truth are selected according to the political friend–enemy logic. Yet that logic, an object of structuring the field of research on politics of force, violence, and punishment, and an interpretative principle of political polarization, is not a logic of truth, nor a legitimate historiographical method, any more than patriotism—however much it may warm our hearts. Form becomes the site of truth when it suits us politically: that is the ironic Schmittian point. It seems that even Schmitt can be invoked against Kelsen when needed—although this is a sentence Lučić, despite being a lawyer by original academic training, cannot understand due to his lack of political-theoretical education. His criteria are Schmittian, which is understandable but not scientifically justified; indeed, it is hypocritical, both humanly and academically. Is it not more honest, like Nathan R. Jessup—the character from a film by Rob Reiner, a recent victim of parricide—whose military logic Ivan Vekić followed (Petković, 2013: 137), to tell the truth, or at least to remain decently silent when everything has long since passed?

Those deemed undesirable and dangerous, even if nationally “ours,” were swept aside in matters central to national politics, sovereign power, and its collectivization. That is how it was, and that is how, in retrospect, it could only have been, because war and the operation of power within it have their own logic. What remains for us is to explain, perhaps to draw a lesson for the future; or at least to attempt something of the sort—and that cannot be done by lying. Just as in Cercas’s modest lesson, which applies both to history and to good fiction, and, after all, in Budiša’s speech at Paradžik’s funeral, which Lučić cites: lies lead nowhere; truth should not be buried, even if it is sometimes complex and forces us collectively to confront what we were and what we are today.[14] If someone like Lučić was already an active and relevant participant in the events in one way or another, is it not more honest at least to open the possibility—if not already to acknowledge—Machiavellianism, akin to Lučić’s language of strategies and tactics with which he so naturally interprets the 1990s, rather than to anniversary-produce energumenic political forgeries that arrive at the conclusion that the deaths of political figures are, like social ownership in the former regime—everyone’s and no one’s?

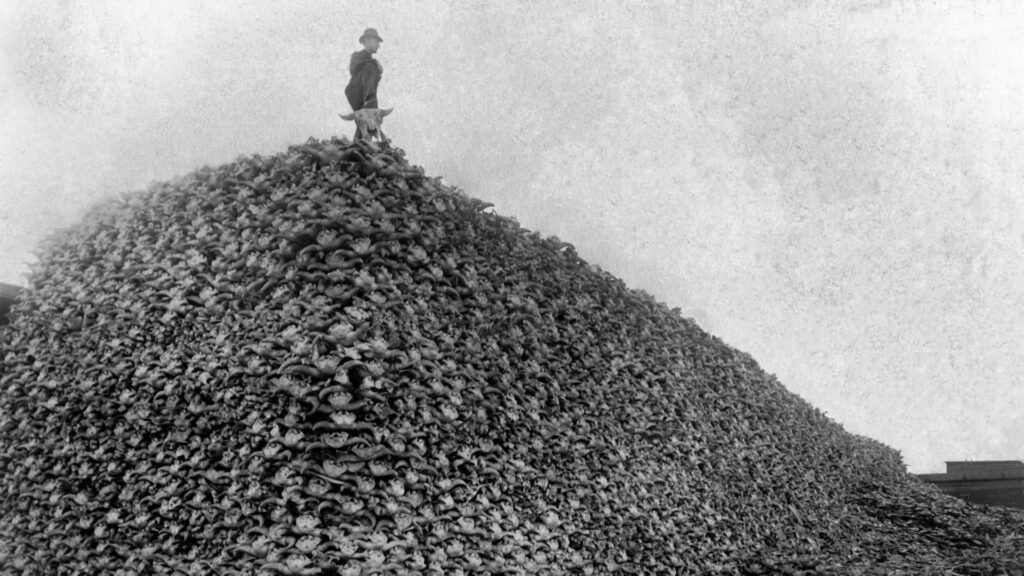

It is difficult to exit political logic.[15] The approach of St Francis, well depicted in Rossellini’s film, as Hesse noted, does not fare well in politics.[16] Yet in the end, it may not be misguided to add a humanistic suggestion to a political mind such as Lučić’s. Courage can be divorced from humanism, politics can be pursued cynically and in silence, but a little compassion does no harm—at least in the sense of Jaspers’s metaphysical guilt—not only when it comes to members of one’s own nation, but to human beings and living creatures in general. Something akin to Williams’s book on the senseless mass slaughter of the buffalo, which carries broader metaphorical potential: “he came to see … destruction … not as a lust for blood … or even at last the blind lust of fury that toiled darkly within him—he came to see the destruction as a cold, mindless response to the life … And he looked upon himself, crawling dumbly” (Williams, 2007: 137).

References

Bjelaković, Nebojša, Strazzari, Francesco, 1999. The sack of Mostar, 1992–1994: The politico‐military connection. European Security, 8 (2): 73-102.

Cercas, Javier. 2017. Prevarant. Zagreb: Fraktura. [Eng. ed. The Impostor: A True Story. New York: Knopf. 2018.]

Despot, Zvonimir. 2011. “TUĐMAN U DNEVNIKU ‘Udba mi je ubila oca i pomajku, a naredba je stigla iz Zagreba’” [TUĐMAN IN HIS DIARY: ‘The UDBA Killed My Father and Stepmother, and the Order Came from Zagreb’], 10th Dezember. https://www.vecernji.hr/vijesti/udba-mi-je-ubila-oca-i-pomajku-a-naredba-je-stigla-iz-zagreba-354693

Filipović, Luka. 2015. “Nekad moćnog Hercegovca danas progone vjerovnici i istražitelji” [Once a Powerful Herzegovinian, Today Hounded by Creditors and Investigators], T-portal, 30th October, https://www.tportal.hr/biznis/clanak/nekad-mocnog-hercegovca-danas-progone-vjerovnici-i-istrazitelji

Foucault, Michel. 1990 [1974]. La vérité et les formes juridiques. Chimères. Revue des schizoanalyses, 10: 8–28. [Eng. ed. “Truth and Juridical Forms,” in: Power, James D. Faubion (ed.), pp. 31–45. New York: New Press. 2000.]

Gaura, Orhidea. 2010. „Ljudi koje je 90-ih trebalo ukloniti“ [People Who Were Supposed to Be Eliminated in the 1990s]. Nacional, 741, 26th January. https://arhiva.nacional.hr/clanak/76462/ljudi-koje-je-90-ih-trebalo-ukloniti

Golek, Kristina, Petković, Krešimir. 2017. Kazna u Krajini. Prilog istraživanju povijesti političke moći i kažnjavanja na području Hrvatske 1991. – 1995 [Punishment in Krajina. A Contribution to the Study of the History of Political Power and Punishment in Croatia, 1991–1995], Časopis za suvremenu povijest, 49 (1): 29-57.

Hayek, Friedrich August von. 1988. The Fatal Conceit (ur. W. W. Bartley III). London: Routledge.

Hesse, Herman. 2015. “Eine Bresche ins Dunkel der Zeit schlagen!“ – Die Briefe 1916-1923 [To open a breach in the darkness of the times: Letters 1916-1923] (3rd from 9 volumes, ed. Volker Michels). Frankfurt a/M: Suhrkamp.

Hrvatske Obrambene Snage. 2018. “HOS: Vinkovci 1991 ubijeni pripadnici HOS a atentat na dr Paragu” [HOS: Vinkovci 1991 – HOS Members Killed and the Assassination Attempt on Dr Paraga], 3rd March. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ypx7a9XkAA

Index.hr, 2015. “A-HSP kazneno prijavio Đapića zbog ubojstva, Đapić: Na takve se gluposti krstim lijevom i desnom” [A-HSP Files Criminal Charges Against Đapić for Murder; Đapić: ‘I Cross Myself at Such Nonsense with Both Left and Right Hand’], 27th January, https://www.index.hr/vijesti/clanak/A-HSP-kazneno-prijavio-Dapica-zbog-ubojstva-Dapic-Na-takve-se-gluposti-krstim-lijevom-i-desnom/797719.aspx

Index.hr. 2025. “Blaž Kraljević 17. rujna 1947. - 9. kolovoza 1992.”, 17th September. https://www.index.hr/vijesti/clanak/tko-je-ubio-blaza-kraljevica/2589149.aspx

Jonjić, Tomislav. 2013. Sporovi i rascjepi u obnovljenoj Hrvatskoj stranci prava 1990. – 1992. (pogled iz provincije) [Disputes and Schisms in the Re-established Croatian Party of Rights, 1990–1992 (A View from the Provinces)] In: Jelaska Marijan, Zdravka, Matijević, Zlatko (eds.), Pravaštvo u hrvatskome političkom i kulturnom životu u sučelju dvaju stoljeća [The Party of Rights in Croatian Political and Cultural Life at the Turn of the Centuries] (pp. 541–563). Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest.

Kasapović, Mirjana. 2001. Demokratska konsolidacija i izborna politika u Hrvatskoj 1990.-2000. [Democratic Consolidation and Electoral Politics in Croatia, 1990–2000]. In: Mirjana Kasapović (ed.), Hrvatska politika 1990.-2000.: izbori, stranke i parlament u Hrvatskoj [Croatian Politics 1990–2000: Elections, Parties and Parliament in Croatia] (pp. 15–40). Zagreb: Fakultet političkih znanosti.

Kasapović, Mirjana. 2020. Bosna i Hercegovina 1990. – 2020.: rat, država i demokracija. Zagreb: Školska knjiga. [Eng. ed. Bosnia and Herzegovina 1990–2000: War, State and Democracy. Zagreb. Školska knjiga. 2024.]

Lalović, Dragutin, 2000. O totalitarnim značajkama hrvatske države (1990.-1999.) [On the Totalitarian Characteristics of the Croatian State (1990–1999)], Politička misao, 37 (1): 188-204.

Lučić, Ivica, n.d. Životopis. [Curriculum Vitae] https://www.sabor.hr/sites/default/files/uploads/%C5%BDivotopisi/PV_HRT/Ivica_Lucic.pdf

Lučić, Ivica. 2016. Političko-sigurnosne okolnosti pogibije Ante Paradžika [The Political and Security Circumstances of the Death of Ante Paradžik], Časopis za suvremenu povijest, 48 (2): 355-388.

Lučić, Ivo. 2017. Vukovarska bolnica: svjetionik u povijesnim olujama hrvatskoga istoka/Vukovar Hospital: a Lighthouse in Historic Storms of Eastern Croatia. Zagreb: Hrvatska liječnička komora i Hrvatski institut za povijest.

Petković, Krešimir. 2013. Država i zločin: politika i nasilje u Hrvatskoj 1990-2012. [State and Crime: Politics and Violence in Croatia 1990–2012]. Zagreb: Disput.

Petković, Krešimir. 2017. Discourses on Violence and Punishment: Probing the Extremes. Lanham, MA: Lexington.

Petković, Krešimir. 2023. Nacionalizam, federalizam i suverenizam: od protubirokratske do protubriselske revolucije? [Nationalism, Federalism, and Sovereigntism: From the Anti-Bureaucratic to the Anti-Brussels Revolution?] Politička misao, 60 (1): 29-50.

Petković, Krešimir. 2026. A Brief History of Sovereign and Disciplinary Power in Croatia. In: Judith Pallot (ed.), Continuity and Change in the Prison Systems of the Former Soviet Union, East Central Europe, and the Balkans. London: Palgrave Macmillan (a chapter accepted for publication in an edited volume).

Poskok.info. 2024. “USTAŠA KOJEG KOMUNISTI VOLE: 11.688 dana UDBA od Kraljevića pokušava načiniti nacionalni mit a njegovu smrt prikazati misterijom” [THE USTAŠA LOVED BY COMMUNISTS: For 11,688 Days the UDBA Has Been Trying to Turn Kraljević into a National Myth and Present His Death as a Mystery] 9th November. https://poskok.info/ustasa-kojeg-komunisti-vole-11-688-dana-udba-od-kraljevica-pokusava-naciniti-nacionalni-mit-a-njegovu-smrt-prikazati-misterijom/

The President, 2020. Documentary series in 10 episodes by Gordan Malić and Miljenko Manjkas [The President] https://tvprofil.com/serije/8824588/predsjednik

Sedlo, Tomo. 2015. “Državno odvjetništvo dvadeset i tri godine štiti ubojice hrvatskih branitelja” [The State Attorney’s Office Has Been Protecting the Killers of Croatian Veterans for Twenty-Three Years]. Hrvatsko pravo: prve online stranačke novine u Republici Hrvatske, 19 March. http://www.hsp1861.hr/vijesti2015-3/19032015-1.html

Sprinzak, Ehud. 1999. Brother Against Brother: Violence and Extremism in Israeli Politics from Altalena to the Rabin Assassination. New York: The Free Press.

Williams, John. 2007. Butcher’s Crossing. Zagreb: Fraktura. [Eng. ed. The Impostor: A True Story. New York: Knopf. 2018.]

Notes

[1] Criticizing, in 2026, a text from 2016 that deals with a book from 2013 does not exactly seem attuned to the accelerated rhythm of global communications, but rather to the prose of Karl May, where one sometimes waits a very long time to return a blow. Fortunately, however, this is not a matter of any kind of vengeful scalping. The polemical opportunity lies in the fact that I am finally completing the book Republic of Punishment: Politics of Violence and Punishment in Croatia 2013–2025 [Republika kazne: politika nasilja i kažnjavanja u Hrvatskoj 2013-2025], which continues where State and Crime: Politics and Violence in Croatia 1990–2012 left off, and this text—adapted for the Annals of the HPD blog—is one of the parts of that study. I might just as well have entitled it “A Letter to the Professor,” since Ivo Lučić is also a professor—moreover, we received the state science award in the same year for our respective books (Lučić, 2017; Petković, 2017): in December 2018, they were presented to us on behalf of the state by the Speaker of Parliament, popularly known as “Njonjo” [Noodle]. Given the subject matter, however, I opted stylistically for a military rather than an academic rank, entitling the note to the brigadier in a García Márquez–like fashion—although, fortunately, the brigadier does have someone to write to, unlike the writer’s colonel, who knows that hope cannot be eaten, but that it is the only thing one can live on. As for ranks, I opted for the more sonorous brigadier (HV), although the biography also mentions the rank of major general (HVO), along with Lučić’s other qualities such as his “consistent commitment to dialogue, respect for and advancement of human rights, and the development of a democratic society and solidarity” (Lučić, n.d.). I therefore trust that he will appreciate this contribution to the public debate on the legacy of the 1990s with special accent on human rights and democracy.

[2] Reasonable academic fact-checking does not, for the purposes of what one seeks to establish with sufficient probability, always need to reach the standards of high-quality and impartial investigative journalism, conscientious archival work, or an independent criminal investigation—although, ideally, at the level of a dense description of the subject matter, and with appropriate methodological caveats, one should be familiar with the events one writes about, so that the logic of the broader picture the researcher seeks to demonstrate is not imposed, by force or negligence, upon the diversity and disorder of contingent and sometimes chaotic social life.

[3] “In an extensive Wikipedia article on Blaž Kraljević, his demise is described together ‘with eight HOS adjutants,’ as well as the cynicism of state policy that posthumously awarded him a decoration for wartime merits” (Petković, 2013: 98). I do not know what is problematic here within a discourse analysis that operates with sources ranging from Kurosawa and Kantorowicz to Večernji list and Wikipedia—except perhaps the term “demise” [pogibija], which, with its fateful epic tone, conceals more banal political operations of power.

[4] The “demise” of Blaž Kraljević—yet another native of Ljubuški, born in Lisice and killed in Grabovica, both near Ljubuški—is politically equivalent to the killing of Ante Paradžik roughly a year later, in the context of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 (for the narrower context relating to the HSP and HOS, see the study by “yet another political scientist”: Veselinović 2019: 147–169, 178–185; for an overview and interpretation of the broader context, concerning the war and its impact on society and the political community, see (another political scientist): Kasapović, 2020; on HOS and Croatian policy in BiH: ibid.; 35, 54–64, esp. note 11, p. 56). The subject of legends and divergent interpretations that speak to contemporary political identity, as well as of differing evaluations and responses to fundamental ethical and epistemological dilemmas regarding the relationship between subject and community, and political sacrifice, structure, fate, and agency—especially in war—nevertheless leaves the factual substrate essentially uncontested, both on Wikipedia pages and in the history of what actually happened, in facts in the basic Rankean historical sense of “how it really/actually was” (wie es eigentlich/tatsächlich gewesen ist). Blaž Nikola “Ero” Kraljević, commander of HOS and also a general of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina, decorated in December 1996 by President Franjo Tuđman with the Order of Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan with gilded interlace, on the proposal of Defense Minister Gojko Šušak, was—together with his entourage—by no means epically but quite mundanely riddled with bullets by members of “Tuta’s Penal Battalion” [Tutina kažnjenička bojna]: Kraljević and eight HOS members were “killed in an ambush by HVO troops led by Mladen Naletilic, allegedly acting on orders from Zagreb” (Bjelaković and Strazzari, 1999: 84). It would nevertheless be an exaggeration to claim that he found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time—except perhaps in the very general sense that applies to all who are killed. See over 200 comments with vivid interpretative twists and political coalitions around Blaž’s specter beneath a commemorative article (Index.hr, 2025), as well as a more freely written critique of the perspective offered by the text’s discursive frameworks (Poskok.info, 2024).

[5] The conference was held in 2011. Unfortunately, I was not present, since the history and politics of the Party of Rights are not a narrower focus of my scholarly research interests. Jonjić writes: “In August 1990, Dobroslav Paraga finally arrived in Croatia from the USA, which marked, one might say, the beginning of a period of a series of assassination attempts against him: hardly a week would pass without news appearing in the press of a press conference or a party statement announcing that the party president had once again been the victim of an assassination attempt from which, by God’s miracle, he had emerged unharmed. Public accusations against Tuđman followed, with the state leadership being accused of betrayal” (Jonjić, 2013: 550). Jonjić is witty, and the sheer frequency leaves room for skepticism; however, humor—especially in the context of the biased narrative of politicians in conflict with Paraga and Paradžik (and the secretary Krešimir Pavelić), as the text itself attests (ibid., esp. 555–563)—still does not amount to a refutation of various more or less drastic claims about assassination attempts, let alone a historiographical or political-science study. Nor does it change anything about the essence of a fatal political reckoning, expressed in the language of Sprinzak’s study of intra-ethnic political violence in the formation of Israel as “brother against brother” (Sprinzak, 1999). For at least one possible event interpreted as an assassination attempt—in which three people were killed and eleven HOS members wounded in an explosion at the HOS headquarters in Vinkovci in 1992—see Hrvatske obrambene snage, 2018; Sedlo, 2015. Regarding the criminal complaint against Đapić in 2015, Đapić stated that he had “crossed himself with both left and right hand” and, unlike Lučić, who wrote an entire article on the topic, concluded: “I have no comment, because every word would only desecrate the memory of Ante Paradžik, a Croatian knight and hero” (Index.hr, 2015).

[6] Given that my academic work has also dealt with revolutions (Petković, 2023), it is academically proper to note that Lučić’s brother Milan was linked in the media to the introduction of “internet revolution” in Croatia (Filipović, 2015).

[7] Ironically, what he wrote about his nebulous opponents also applies to Lučić himself: “systematically ignoring facts and reality … Such people seek simple (and to them acceptable) answers to complex social questions” (Lučić, 2016: 383).

[8] See Petković, 2013: 41–88. Prediction within a theoretical framework and parallels with other comparable aggregate cases do not in themselves constitute factual proof of a particular killing, but they do shift the burden of proof and open up strong suspicions, especially given its unusual circumstances and its wartime and political context.

[9] See Lučić’s narrative of the three “checkpoints”—Dugo Selo, Sesvetska Sela, Sesvete (Lučić, 2016: 363–368).

[10] I recommend to Lučić a neo-Nietzschean epistemological classic from the 1970s on this issue, devoted to truth and juridical forms, which addresses the manner of “producing truth, establishing juridical truth” [produire la vérité, d'établir la vérité juridique] by linking knowledge to the struggle for power: “Political power is not absent from knowledge; it is interwoven with it” [Le pouvoir politique n'est pas absent du savoir, il est tramé avec savoir]“ (Foucault, 1990: 12, 28). Leaving aside Oedipus, the psychoanalytic problem, and general epistemological questions concerning the relationship between knowledge and power, in this case and with regard to Lučić’s political interpretative method, this remains a valid maxim.

[11] The President, HTV 1, 27. siječnja 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rp1uTgeQwQI, 24:00-28:10.

[12] On assessments of the 1990s regime from the contemporaneous perspective of normative political theory and comparative politics in Croatia, with regard to distinctions between liberal democracy and authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, see Lalović, 2000: 202; with editorial note, 188; Kasapović, 2001: 17–24.

[13] See Tuđman’s diary narrative of the event to which Lučić refers (Tuđman, 1986 in: Despot, 2011). It is not my intention to enter into a debate about the facts of that event, but rather to point out Lučić’s inconsistency in accepting official narratives—indeed, in that case his interpretation seems to me more convincing, unlike the one concerning Paradžik. On moments of the exercise of sovereign power throughout history, from the Habsburgs through the Yugoslav royal regime, the Ustaša and communist regimes, to independent Croatia, through a “Schmitt–Foucault” interpretative lens, I discuss in: Petković, 2026. In parallel with Croatia (Petković, 2013), the same interpretative framework is illustratively applied to the insurgent Serb regime; see Golek and Petković, 2017.

[14] In his funeral speech for Paradžik, Budiša stated: “with you, not a single lie must be buried in the grave, nor any concealed truth” (Lučić, 2016: 370). If one may paraphrase Cercas—although, unlike him, I believe it is more likely that reality saves and fiction kills (the colonel would agree that hope is not fiction; about the brigadier, I am not sure): although great art undoubtedly does this, the task of science is to bring us closer to truth, “to show us the complexity of life, with the aim that we ourselves become more complex; to analyze how evil functions so that we might avoid it, perhaps even how good functions so that we might learn it,” and the scholar, after all, does not have “permission to lie” (Cercas, 2017: 16, 18). Cercas’s book about the syndicalist Enric Marco is, in my view, one of the finest books on historical memory and the industry surrounding it: through the theme of a pathological liar who for a long time successfully deceived the public into believing he had been a survivor of Flossenbürg, he speaks about the general conditions of political lying within a nation that bears many interesting similarities to Croatia, with one crucial difference—the fascist side won the war against the communists, rather than the other way around.

[15] I note, lest it be misunderstood—as in State and Crime (Petković, 2013: 73–74)—that the interpretation of the 1990s is not a normative debate of hindsight or facile political moralizing about the past in the service of present conflicts, nor about the justification of particular wartime policies in which many people on different sides and in different circumstances lost their lives. Whatever republic one constructs today and seeks to defend normatively is itself an expression of possibility, of a peacetime context, of a moment that can hardly escape political logic, which, as Hobbes and Schmitt knew, is the logic of the political. The Schmittian—and in my case (in contrast to Hobbes) Foucauldian because of types of power and technologies of governance, hence Foucauldian–Schmittian—matrix is analytical, not normative. People embedded in collectives struggle for power, and there are connections between war and politics, with politics being at least as much a continuation of war (Foucault) as war is a continuation of politics (Clausewitz). This is therefore not a justification of various failed ideological conceptions in a seismically unstable field of civilizational, national, and imperial conflicts, nor even of a utilitarian policy of a national collective that, in self-preservation, sacrifices individuals who endanger the whole—which, as in the logic of lapot, a ritual killing of the old and weak members of the group, must be preserved beyond the peacetime vulgate of human rights (cf. Hayek, 1988: 152). It is a matter of truth in the most basic sense, in which statements must not falsify or circumvent facts that do not suit them.

[16] Hesse’s politically lucid remark in a letter to Rolland was that the application of love to political matters is doomed to failure (Hesse, 2015: 105).